The Scholar Who Unearthed a Forgotten Empire - James Prinsep

James Prinsep was the son of John Prinsep, a merchant of the East India Company. John Prinsep arrived in India in 1771, made a fortune in the indigo trade, and returned to England in 1787 to settle as a company merchant. He even became a Member of Parliament but later faced financial losses due to business fluctuations. Leveraging his trade connections with India, John secured various positions for his children in the East India Company. James Prinsep, his tenth child (seventh son), was born on August 20, 1799, in Bristol. He briefly studied architecture. Upon learning of vacancies for quality control officers in the Indian mints, John sent James to train under Robert Bingley, a quality control officer at the London Royal Mint. Acquiring expertise in coin quality assessment, James joined the East India Company’s Calcutta Mint as a quality control officer in 1819.

Traveling aboard the ship Hooghly, James Prinsep set foot in Calcutta on September 15, 1819. His brothers, William Toby and Henry Toby, already working in India, warmly welcomed him. At the Calcutta Mint, he was appointed as an assistant to H.H. Wilson (who later cataloged around a lakh pages of manuscripts, over ten thousand coins, and other collections gathered by Colin Mackenzie after his death). Initially, James attended a few Asiatic Society meetings but wrote to his father that they did not spark much interest. He met local luminaries like Dwarkanath Tagore (Rabindranath Tagore’s grandfather) and Raja Rammohan Roy. James had a keen interest in modern chemistry and aspired to convince the East India Company to establish a modern science laboratory in Calcutta to experiment with the properties of substances like salt, opium, and nitre. A speech he delivered at an Asiatic Society meeting on “modern scientific discoveries” earned him great acclaim among Calcutta’s elite.

1. Appointment in Benares

In 1820, James Prinsep was appointed as an officer at the newly established Benares Mint. Traveling 800 miles from Calcutta by boat, he reached Benares in November and assumed his duties as a quality control officer. Finding his official residence unappealing, he made architectural modifications, which impressed other European officers in Benares and earned him respect for his construction skills. He was soon sought for architectural advice. He set up a laboratory in his residence for scientific experiments, where he invented a pyrometer to precisely measure furnace temperatures for melting metals for coins and a sensitive scale capable of weighing a thousandth of a grain. These innovations earned him a Fellowship at the Royal Society in 1828.

James would wake at dawn, complete office work by breakfast, and head to the mint three miles away to conduct inspections and oversee tasks. He returned to his bungalow by 10 a.m. to avoid the midday heat, leaving the rest of the day free. This allowed him to undertake numerous projects in Benares, including:Spending two years creating a detailed map of Benares.

Overseeing the construction of a church funded jointly by local Europeans and the East India Company.

Serving as secretary of the Benares Development Committee in 1823, when the Company allocated funds for regional development. He proposed and supervised road-widening projects without damaging buildings.

Addressing Benares’ drainage issues, as low-lying areas accumulated water during the monsoon, making the town filthy. Using development funds, he constructed an underground tunnel for sewage drainage, built beneath multi-story buildings without harming their foundations, earning widespread praise.

When Benares residents gifted him land, he leveled it and donated it back for a local market. This centrally located land was highly valuable, yet James, a modest Company employee, gave it freely.

Restoring the dilapidated Alamgir Mosque, built by Aurangzeb in Benares, by strengthening its foundations.

Convincing skeptics to build a bridge over the Karamnasa River, funded by a wealthy Hindu merchant at a cost of one lakh rupees. Despite concerns about unstable soil and floods, and local beliefs that crossing the river was inauspicious without a Brahmin’s assistance, James oversaw its construction, proving its resilience against heavy floods.

Conducting the first population census of Benares.

An accomplished artist, James painted scenes of Benares’ streets and ghats, which were published in England in 1825 as Illustrations of Benares. His painting of the historic Gyanvapi Mosque, partially built within the Kashi Vishwanath Temple, is notable.

2. Transfer to Calcutta

When Governor William Bentinck expanded the Calcutta Mint and closed the Benares Mint, James Prinsep was transferred to Calcutta in 1830. By then, his brother William Toby’s finance company, Palmer & Co., had gone bankrupt with debts of three million rupees, and its assets were seized and auctioned by the government. James took in and supported Toby’s destitute family. While supervising the Salt Water Lake canal project, his brother Thomas fell from a horse, slipped into a coma, and died in 1830 without recovering. This canal project, aimed at improving waterways around Calcutta for transport, was halted by Thomas’ death. On Governor Bentinck’s suggestion, James completed it.

In 1830, James fell in love with a woman named Lucy, but upon learning she loved another, he kept his feelings to himself and remained unmarried for years. On April 25, 1835, he married Harriet, the daughter of a Bengal Army colonel. They had a son and a daughter, but their son died in childhood.

3. Guiding the Asiatic Society

In 1831, on the advice of his superior H.H. Wilson, James joined the Asiatic Society as a member. He was immediately drawn to the thousands of ancient coins piled up there, collected from excavations across Company-controlled India and sent to the Society for research by regional officers. Many were gold coins. James began studying them, approaching numismatics scientifically. He classified the coins into Persian, Bactrian, Hindu, Greek, and Sinhalese categories and wrote numerous articles.

Over six years, these articles were compiled posthumously into a two-volume book, Essays on Indian Antiquities, Historic, Numismatic and Palaeographic, James Prinsep.

When H.H. Wilson left for Oxford in 1832 to teach Sanskrit, James took charge as the chief officer of the Calcutta Mint and secretary of the Asiatic Society. As mint officer, he introduced a revolutionary change by replacing silver rupees with copper rupee coins for the first time. One side bore the head of British Emperor William IV, and the other the East India Company’s name. James designed these coins, which entered circulation in 1835, and used a steam engine for minting them, a first.

As Asiatic Society secretary, he renamed it the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The Society published an official journal, Asiatick Researches, while another journal, Gleanings of Science, was on the verge of closure. James merged the two into the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (JASB) and invited amateur historians across India to submit research papers reflecting India’s history and culture, using JASB as a platform.

During the colonial period, thousands of in-depth research articles on India’s historical and cultural aspects were published in this journal, playing an unparalleled role in scientifically evaluating Indian history rather than relying on myths. The Asiatic Society continues today under its original name.

As secretary and editor of the Society’s journal, James’ intellectual curiosity soared. The Society received daily reports of inscriptions, coins, sculpture replicas, and other archaeological discoveries from across India. Great scholars sent their research for publication, and James formed connections with them. This sparked his profound interest in ancient Indian knowledge and history, leading him to dedicate his time and intellect to studying India’s past.

4. Brahmi Script: The Key to Ancient Indian History

While James Prinsep’s earlier contributions to society were significant, deciphering the mysterious Brahmi script was a monumental achievement, cementing his legacy as one of the most influential figures in Indian history.

Due to some people’s envy and hostility, a script had become nearly extinct, but James Prinsep revived it. Just as the Rosetta Stone transformed our understanding of ancient Egyptian culture, deciphering the Brahmi script brought centuries of hidden ancient Indian history to light.

James Prinsep resurrected a great empire forgotten due to envy and hatred. Emperor Ashoka, the architect of a united India, ruled an empire stretching from Kashmir, Nepal, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh to Tamil Nadu. He erected pillars with inscriptions at his empire’s borders, yet his name was absent from Hindu historical records, puranas, or royal genealogies. James Prinsep reintroduced Ashoka’s name into history.

His role in reviving Buddhism, a heritage of this land pushed into obscurity due to envy and hatred, is unforgettable.

These three achievements are James Prinsep’s gifts to Indian history. By the 18th century, Ashoka’s pillars and inscriptions, their language, and the Buddhist statues unearthed everywhere were incomprehensible. Some curious East India Company officers tried to understand them, but received vague answers: Ashoka’s pillars were Bhima’s mace, their inscriptions were “Brahma’s writing,” and Buddha’s statues were Vishnu’s tenth avatar or symbols of a misguided religion. By deciphering the Brahmi script, James Prinsep shattered this ignorance.

Scripts in India

Scripts are evident in India at least since the Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE to 1300 BCE). A script is distinct from a language. Languages like English, French, Italian, and German use the Roman script, while Hindi, Sanskrit, Marathi, Nepali, and Sindhi use the Devanagari script. Similarly, Pali, Gandhari, and Magadhi were written in the Brahmi script.

From the 5th century BCE, the Brahmi script was in use in ancient India, considered indigenous to its people. By the 3rd century BCE, during Ashoka’s reign, it was at its peak, with all his inscriptions written in Brahmi, known as Ashokan Brahmi. Common people could read it then (evidenced by a 2nd-century BCE terracotta sculpture of a child learning Brahmi). However, by the 4th century CE, regional variants like Tamil-Brahmi, Gupta-Brahmi, Kalinga-Brahmi, and Bhattiprolu-Brahmi emerged, causing people to gradually forget the original Ashokan Brahmi.

The Chinese traveler Faxian, visiting India in the 4th century, recorded unrelated tales told by locals about an Ashokan Brahmi pillar in Pataliputra, suggesting the script was no longer readable. Similarly, 7th-century traveler Xuanzang described Ashokan pillars but could not interpret their Brahmi inscriptions.

Firoz Shah Tughlaq (1309–1388) was astonished by a 42-foot Ashokan pillar in Topra, Haryana, and ordered it transported to Delhi. Moved on a 42-wheeled vehicle to the Yamuna River and then by boat, he sought to understand its inscriptions. Scholars claimed the pillar was Bhima’s staff, left in Topra after the Mahabharata war, with inscriptions stating, “No one can move this pillar until Emperor Firoz Shah arrives.” This reflected not only their deceit but also the absence of anyone, even among scholars, who could read Brahmi.

By the 18th century, many Europeans devoted their time and intellect to understanding Indian history without expecting rewards. Ancient inscriptions, especially in Brahmi, were indecipherable. In 1781, Charles Wilkins deciphered a 9th-century Brahmi inscription due to its similarity to the modern Bengali script, but this did not help decode the older Ashokan Brahmi. William Jones, inspired by Wilkins, tried but failed to make progress.

For three more decades, no progress was made until James Prinsep began working on the Brahmi script in 1834, fully deciphering it within five years through various stages.

A. First Stage

While working in Benares, James visited the Allahabad Fort and saw a large pillar outside, exposed to sun and rain, with fading inscriptions. Recognizing Emperor Jahangir’s name among them, he deemed it historically valuable and obtained a copy of the inscriptions through TS Burt, an officer in Allahabad, for study.

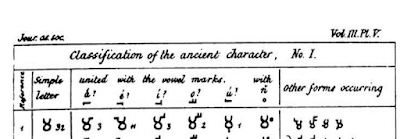

Locals called the pillar “Bhima’s mace.” It bore three inscriptions from different eras: Ashoka’s in Brahmi, Samudragupta’s (c. 335–375 CE) in Sanskrit recording his victories, and Jahangir’s in Persian. In 1834, James wrote an article, Note on Inscription No.1 of the Allahabad Column, breaking thirty years of silence on Brahmi script research. He proposed:Brahmi is an abugida script, where letters combine with vowels and diacritics to form compound letters, like Telugu (unlike English, where each letter is fixed).

He counted the frequency of each letter in the inscription, noting that one letter, e.g., 𑀫 (ma), appeared 32 times, with variants like 𑀫𑀸 (mā) 3 times and 𑀫𑁂 (me) 11 times, identifying a pattern closer to Prakrit than Sanskrit.

Brahmi includes vowels and consonants.

B. Second Stage

In the first stage, James identified the letters and their patterns but not their pronunciation. After reading his Allahabad article, Hodgson sent copies of inscriptions from Mathiah and Radhai near Nepal, noting their similarity. With three Brahmi inscriptions—Allahabad, Mathiah/Radhai, and Firoz Shah’s Delhi pillar—James studied them and wrote another article in 1834, observing:Pairing 𑀢𑀸 (ta) with 𑀬𑀸 (ya) forms 𑀢𑁆𑀬𑀸 (tya), a compound letter.

All three inscriptions began with 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀦𑀫𑁆𑀧𑀺𑀬𑁂 𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺 𑀮𑀚, read as “Devanampiye Piyadasi laja” (Beloved of the Gods, King Priyadarshin). Unaware it referred to Ashoka, he speculated it could be a victorious king’s name, a religious phrase, or significant to Buddhists or Brahmins—speculations that were largely correct.

C. Third Stage

No progress occurred for two years. In 1836, Norwegian scholar Christian Lassen wrote about bilingual coins of Indo-Bactrian king Agathocles (190 BCE). After Alexander conquered parts of northwest India, his generals’ descendants, like Agathocles, ruled Gandhara. His coins bore his name in Greek (Basileōs Agathokleous) on one side and Brahmi (Agathukla raja) on the other. Knowing Greek, Lassen correlated the scripts.Inspired, James, an authority on ancient coins, reexamined his bilingual coins in Lassen’s method, decoding more Brahmi letters.

He noticed Sanchi donation inscriptions ended with 𑀤𑀸𑀦𑀁, likely “dānam” (donation), correctly identifying two more letters.

Brahmi began revealing itself. The recurring opening phrase “Devanampiye Piyadasi laja” astonished him, suggesting a king whose empire spanned the subcontinent, yet no Hindu puranas or genealogies mentioned “Devanampriya.”

The answer came from the 3rd-century CE Pali text Dipavamsa from Sri Lanka, translated by British officer George Turnour. It mentioned “Piyadassi … who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and own son of Bindusara.” Turnour sent this to James and wrote an article in the Asiatic Journal, confirming “Devanampiye Piyadasi” referred to Ashoka.

Recognizing Brahmi’s link to Pali, James, with assistant Ratna Paul, fluent in Pali, fully deciphered Brahmi and later the related Kharoshthi script.

In 1837, he fully decoded all seven Ashokan inscriptions on Firoz Shah’s pillar, publishing them in the Asiatic Journal.

In 1837, he deciphered two Ashokan inscriptions from Gaya, held in the Society’s library for forty years, attributed to Ashoka’s grandson, Dasharatha, a Magadha king.

He identified key events in Ashoka’s reign from various inscriptions.

Across inscriptions, the opening phrase “Devanampiye Piyadasi laja” (Beloved of Gods, King Piyadasi) and closing “havam aha” (Thus spake) formed: “Thus spake King Piyadasi, Beloved of the Gods.”

5. Premature Departure

From 1838, James Prinsep’s health declined, with severe headaches and fever. His doctor misdiagnosed it as a bilious condition, and treatments failed. Hoping a change in climate might help, James abruptly halted his research and sailed for England. The sea journey and salty air worsened his condition. He arrived in England frail, stayed with his sister for a year, but a worsening brain condition led to his death on April 22, 1840, at age 40.

His twenty years in India were remarkably fruitful. Friends mourned his death and built a memorial building in his name on the Ganges’ banks, now a tourist site in Calcutta. His research papers were published as books, and the National Portrait Gallery in London created a bronze medallion in his honor.

James Prinsep’s relentless curiosity, unwavering dedication, problem-solving zeal, and hard work remain inspirational. His extraordinary effort in deciphering a language, reviving Emperor Ashoka and his vast empire after nearly two millennia of obscurity, has etched his name in history. Unearthing India’s authentic history, buried for about fifteen hundred years under myths and fabricated tales, makes James Prinsep truly worthy of remembrance.

By Bolloju Baba

Footnotes

[1] Founded by British lawyer and orientalist William Jones on January 15, 1784, the Asiatic Society aimed to research Asian history, culture, languages, and sciences.

[2] Ashoka in Ancient India, Nayanjot Lahiri, p. 300.

[3] Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, Romila Thapar, 2012, Foreword, p. 8.

[4] Note on Inscription No.1 of the Allahabad Column, Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. III, 1834, p. 114.

[5] Note on the Mathiah Lath Inscription, JASB, Vol. III, 1834.

[6] JASB, Vol. 5, 1836.

[7] J. Prinsep, Note on the Facsimiles of Inscriptions from Sanchi near Bhilsa…, JASB, Vol. VI, 1837.

[8] George Turnour, Further Notes on the Inscriptions on the Columns at Delhi, Allahabad, Betiah, etc., JASB, Vol. VI, 1837.

[9] An inscription with Ashoka’s name was found in 1915 at Maski, Karnataka, reading “Devanam Piya Ashoka.” Another from 1954 at Gujjar, Madhya Pradesh, reads “Devanam Piyadasi Ashokaraja.”

[10] Interpretation of the Most Ancient of the Inscriptions on the Pillar called the Lat of Firuz Shah…, JASB, Vol. VI, 1837.

[11] James Prinsep, Facsimiles of Ancient Inscriptions, JASB, Vol. VI, 1837.

References Essays On The Antiquities Of India, James Prinsep, Vol. I.

Ashoka in Ancient India, Nayanjot Lahiri.

Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, Romila Thapar, 2012.

Ashoka, The Search for a Lost Emperor, Charles Allen.

The Search for the Buddha: The Men Who Discovered India's Lost Religion, Charles Allen.

Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, various volumes.

Inscriptions of Asoka, Vol. I, E. Hultzsch.

The Archaeology of South Asia, from Indus to Asoka, Robin Coningham and Ruth Young.

allthingsindology.wordpress.

Wikipedia.

No comments:

Post a Comment