The Elusive Horse: Unraveling Claims of Vedic Antiquity in the Indus Valley

In the tapestry of India’s social and cultural evolution, the Indus Valley Civilization (Harappa), flourishing between 2600–1900 BCE, stands as the earliest known milestone. Following this, from 1500–500 BCE, Vedic religion emerged, with the composition of the Vedas laying the groundwork for Brahmanism. Initially pastoralists, the Rigvedic Aryans transitioned to agriculture by clearing forests. As Vedic religion waned, urban centers grew, giving rise to the Shramana traditions of Jainism and Buddhism, which challenged Vedic orthodoxy. By the 6th century CE, Vedic religion absorbed various worship practices, evolving into Puranic Hinduism.

Brahmanical narratives often claim Puranic Hinduism as the world’s oldest religion, asserting that all faiths stem from it and tracing its origins back millions of years. To bolster this, some argue that the Indus Valley people practiced Vedic religion, pushing the Vedic timeline beyond 1500 BCE. However, this claim hinges on a critical piece of evidence: the horse, extensively described in the Vedas alongside spoked-wheel chariots. The absence of horses in the Indus Valley poses a significant challenge, as the horse is not native to India and was introduced by the Aryans from outside.

The Vedic Aryan society was pastoral, reliant on horses, while the Indus Valley civilization was agrarian, unfamiliar with them. Archaeological evidence shows horses appearing in India only after the decline of the Indus Valley civilization, a fact that undermines Brahmanical assertions. In 1931, Sir John Marshall clearly stated that Vedic Aryans lived later than the Indus Valley people.

Where Did the Horse Come From?

Modern research pinpoints the domestication of the horse to the Pontic-Caspian steppe (modern-day Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan) around 2200 BCE. A study led by Ludovic Orlando, analyzing 273 ancient horse genomes, confirms that horses spread across Asia and Europe shortly thereafter. By 1800 BCE, archaeological sites in Asia reveal horse skeletons and spoked-wheel chariot remains, coinciding with the complete decline of the Indus Valley civilization. This supports the Aryan migration theory: around 2000 BCE, Yamnaya steppe pastoralists from the Pontic-Caspian region entered India on horse-drawn chariots, bringing pre-Sanskrit and pre-Indo-Aryan languages that evolved into Sanskrit and other Indian languages. These were the Rigvedic Aryans, whose texts mention horses over 200 times.

No Horses in the Indus Valley

Despite extensive excavations, no horse skeletons, bones, or clear depictions have been found in Indus Valley sites. Among the numerous terracotta figurines unearthed, none definitively represent horses. One figurine is cited as a horse, but its identity—possibly a goat or another animal—remains ambiguous. Hundreds of Indus Valley seals depict elephants, tigers, bulls, rhinos, and antelopes, but not a single horse. Horse bones appear in the region only from 1500 BCE onward, aligning with the arrival of Rigvedic Aryans and their chariots. This evidence contradicts claims of Vedic continuity from the Indus Valley, yet some Brahmanical scholars resist acknowledging their foreign origins, insisting they are indigenous descendants of Vedic-practicing Indus people. Modern genetic and linguistic studies further weaken these claims.

Brahmanical Arguments and Their Flaws

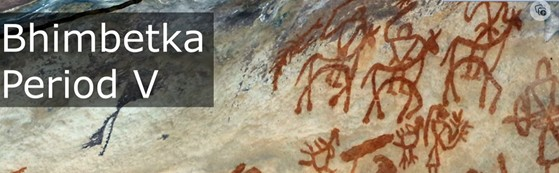

- Bhimbetka Cave Paintings: Located in Madhya Pradesh, Bhimbetka’s rock art spans from the Stone Age to the medieval period, with some paintings dated over 7,000 years old. Some claim these depict horses, suggesting their presence in India for millennia. However, horse imagery appears only around 300 BCE, not in the earliest layers, offering no proof of ancient horses in India.

- Sinauli Chariot (2018): Excavations in Uttar Pradesh uncovered a chariot, which team leader Sanjay Manjul claimed was horse-drawn. However, the chariot has solid wheels, not the spoked wheels characteristic of Aryan chariots, as noted by Indologist Edwin Bryant. No horse remains were found nearby, and the chariot’s draft animals—possibly oxen—remain unidentified.

- Surkotada “Horse” (1974): A supposed horse bone (Equus caballus) from Surkotada, Gujarat, was dated to pre-Vedic times by Sharma (1974). Richard Meadow (1987) countered that it likely belonged to a donkey, and carbon dating raised doubts. The bone came from upper layers of the site, requiring further study.

- Harappan Horse Seal (1999): NS Rajaraman claimed evidence of horses in Harappa, including a horse seal. Harvard Indologist Michael Witzel debunked the seal as a digitally fabricated hoax.

Conclusion

Claiming beliefs date back thousands or millions of years requires robust evidence. Archaeological, linguistic, and genetic data must substantiate arguments to withstand scrutiny from global Indologists. Without such evidence, claims risk being dismissed as hoaxes. The absence of horses in the Indus Valley, contrasted with their prominence in Vedic texts, underscores the distinct timelines of these societies. The search for a horse to bridge this gap remains futile, affirming the Aryan migration as a historical reality.

By Bolloju Baba

No comments:

Post a Comment